I hope you take time to feel all there is that’s offered because the fertility of the senses RIGHT NOW will not return. It’s precious. It asks for nothing but your presence. I have the sense that’s why we feel so tired when someone we love deeply dies—so we’ll float in the deep end for awhile and forget about exerting ourselves.

--Gail Baker(1)

Thanks to my friend for the reminder that with death comes some kind of opening—cracks through which we glimpse our inner life, or the hearts of our loved ones, or different dimensions of awareness.

I keep feeling that I am ready to return to my usual life, but one thing after another interferes. Most recently, I got sick enough to stay in bed for several days. Though I felt terrible, I also knew I was longing for time to reflect and write, and honestly just time to do nothing. It felt so good to just lie in bed and allow. To let everything flow through me. To just feel everything that has happened.

*******

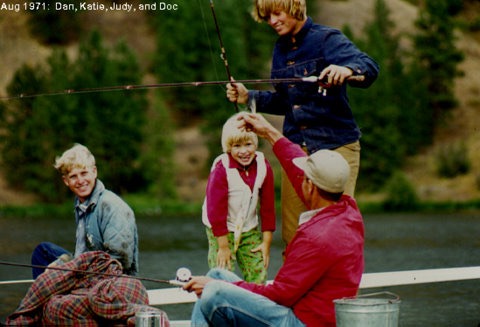

My brother asked me the other day what would I have been writing in my blog if I hadn’t been worried about what Dad would think? At first I don’t know how to answer the question. There is a little girl inside me squirming and stubbing her toe and mumbling, “Oh…just stuff…”

Good grief! I think. Get a grip on who you are, lovely one! This is an important question he is asking you! And maybe he really wants to know. Maybe your Dad wanted to know, too, and didn’t know how to ask. And, besides, whether anyone wants to know or not isn’t even the point. You know who you are. Speak up!

When I was young, my subjective inner world was hard to talk about. I lived it inside myself in my life with books, but my emotions, my personal will, my creativity, and my spirituality were all things that I felt cut off from in the outside world. It’s no wonder, when I think about it, that I became a therapist who could help people value those things in themselves. Our greatest gifts often begin with a wounding.

Now I treasure my subjectivity. This is how I know who I am and what matters to me. It is the root of my unique contribution to the world. It is the rich variability between people we need as a species. And it is those subjective experiences I am wanting to talk about here today.

*******

Five days after Dad died, my sister sent me a text with the quote from H.D. that ends the last post I wrote before Dad’s death.

…last night

was the first night that it came,

the distant summons, the muted cry, the call,

and my bones melted and my heart was flame,

and all I wished was freedom and to follow…

--H.D.(2)

And she brought tears to my eyes by writing, out of the blue: This quote from your blog sounds like Dad saying goodbye.

*******

The night before Dad passed, I lay awake unable to sleep. As I lay there I could feel my body quivering and shaking slightly with the anxiety of knowing he was in the hospital, of my rush to make travel arrangements for the next day, of trying in vain to relax and get some rest. At some point—late, and very unexpectedly— there was a feeling as though a tremendous wing of joy had passed over me in the dark. Then just as quickly as it came, it was gone, leaving me with my own anxious restlessness again.

I have no idea what this was. All I can say is what it felt like. And I say this knowing that it may only hold meaning for me. But it felt to me like some kind of presence. It felt like Mom waiting for Dad. Like the energy of all our loved ones out there waiting for us. Like Dad recognizing this was there for him.

If you knew my Dad, you would know how big a leap this is to make. If you knew how much of his life he spent arguing against the offenses of religion, the way that it has historically separated us from each other, the violence done in the service of specific beliefs. Yet Dad always believed in love, and knew that there is power in love. He didn’t often talk about it, and his love was often obscured by his strong personality, but it was always there at the center of who he was.

*******

When I would visit for a weekend when we were caring for Mom at the rehab center, Dad would spend the night with her and I would drive in from the farm house in the morning to replace him for the day. One day as I was leaving the house, I noticed that he had left a lawn sprinkler on overnight. I thought he might have forgotten about it, so I shut it off when I left, not realizing that if the pump was still on without any sprinklers running it could ruin the motor. When I met Dad that morning and told him about the sprinkler he got mad at me and hollered at me in the hallway of the rehab center, “You have to trust me!” This startled me and hurt—especially because I was trying so hard to do the right thing—and though I could understand why he was short-tempered, his reaction upset me for the rest of the weekend.

At first when I thought about it, the idea of me trusting him seemed ridiculous. We were all stressed, and he was 90 years old and had been forgetting all kinds of things—I would find the stove on hours after breakfast or the water running after he had left the bathroom. And he wants me to TRUST him? On what grounds? I felt like shouting back at him.

But that statement stuck in my head, and over time I got curious about it. Did I trust Dad? What does it mean to trust someone? Was he talking about something deeper than his lawn sprinkler? I started using that as a kind of barometer for my actions in the last years that Dad was alive. What would I do right now if I did trust him?

One day last summer I happened to hear Dad throwing up. When I came to the bathroom door and asked him how he was doing he admitted that he wasn’t that keen at the moment. He had taken some old supplement that had been open for awhile and he thought that had disturbed his digestion. But when I asked him if he needed any help, he said that he didn’t. Just let me suffer on my own, was the gist of his response. Ok, Dad. I will trust you. And I went off to bed.

Or when I took over moving his lawn sprinklers this summer when he got too unsteady on his feet, I thought I would just go figure it out on my own, but Dad had all the details down to the inch—where to place the sprinklers, how large to make the hose coil when I was finished, what order to move the sprinklers in. Everything had its place and its purpose. In the past I would have felt constrained and offended, but pretty soon I realized that I could just trust him. And as obsessive as his system was, it did actually work. All the lawns got watered in a short amount of time. His hose never had those annoying kinks in it. And after I started trusting him I could relax and follow him around as he showed me exactly where to place the sprinklers, and just enjoy doing something together with him.

I am finding that his request to trust him doesn’t end with death. As we are cleaning out the house and I am deciding what to keep and what to throw away, I start hearing those words again in my mind. Only this time they aren’t angry. Now they are kind. Warm. Comforting. Trust me, I hear. Which now translates into: It’s ok to let go of things. What needs to be done will get done. I have taken care of the things that were important to me…save what you want and get on with your own life.

*******

Virginia Woolf’s father died tragically and early, when she was in her 20’s, and though she was devastated at the time, she reflects in her diary much later that if her father had lived it would have been the end of her literary life. "No writing, no books;--inconceivable." (3) I have to say that I recognize her feelings. I am thankful for the years I had with my parents—that they got to know my husband, and saw me become part of my community in Seattle and find work that I loved. But I am also grateful to be so young when they died. I feel like there is possibility for me to focus on my own life and my own calling—and perhaps specifically on writing. I don’t think it is a coincidence that I have written so much since Dad died. There's room for books now that there may not have been room for before—at least not inside my own head.

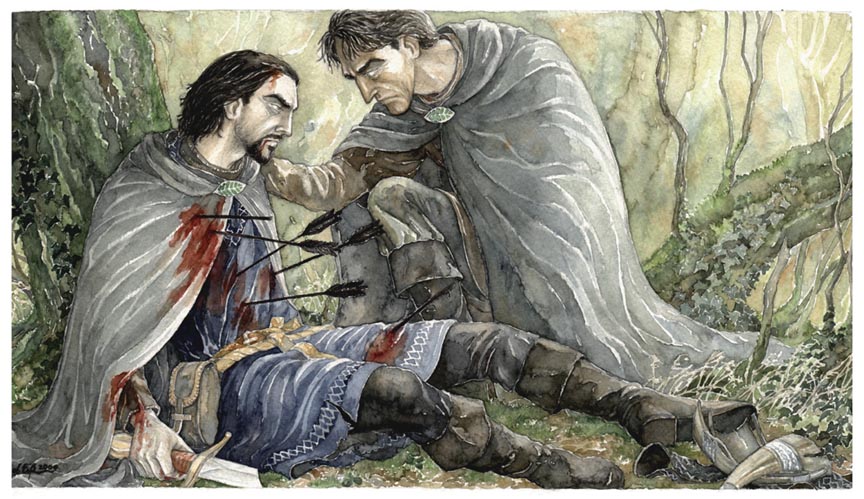

But the expansion I am feeling isn’t only about not having the extra duties of caring for an elderly parent, or the loosening of old identity. I have also had the sense—first after Mom died, and now also after Dad’s passing—that when someone close to us in our family dies, it makes something available to us. It feels like there are “family resources” created by the lives of my ancestors that are stored up for me to use, and that when a person passes, the key to those resources is passed on to the next generation.

I don’t even really know what I mean when I say this, or how to put it into words. Anything I say is certainly meant as the finger pointing at the moon. But it feels like there is some kind of reservoir of love, patience, kindness, wisdom—certainly way more than any person showed in their actual life—that is available to me now to draw from, and that I will pass on when I die.

So their passing gives me this gift. Not only the gift of time and space, and the perspective to see myself more accurately in relation to them, but the gift of support. As I am quiet and listen, I can feel energies coalescing around me in new ways. I am surprised today to realize that what I feel, even in the midst of sadness and grief and uncertainty, is power. The power of knowing who I am. And the power to create from that.

*******

I open one of the books of poetry that I bought recently in Fruita and read:

In the depth of the ground

my soul glides

silent as a comet (4)

Yes, I think. That is how it would be for Dad.

------------

(1) www.gailbakerartmaker.com

(2) p. 61, H.D., (1972). From "Sagesse" in Hermetic Definition. New York: New Directions.

(3) p. 17, Virginia Woolf, quoted in Tillie Olsen, (2003). Silences. New York: Feminist Press.

(4) p. 217, Tomas Tranströmer, (2006). the great enigma: new collected poems. Translated by Robin Fulton. New York: New Directions.

July 13, 2019

July 13, 2019

Ecology

Ecology