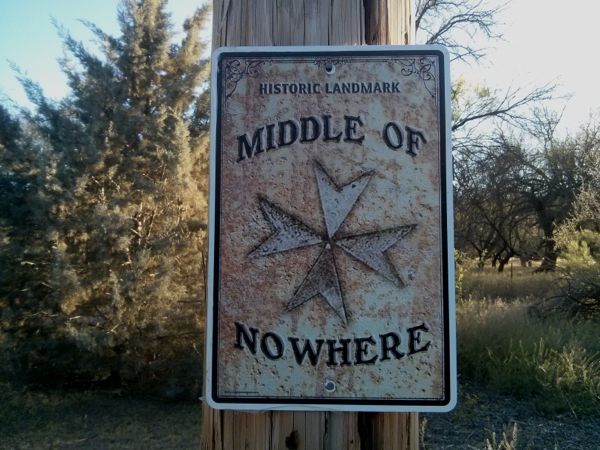

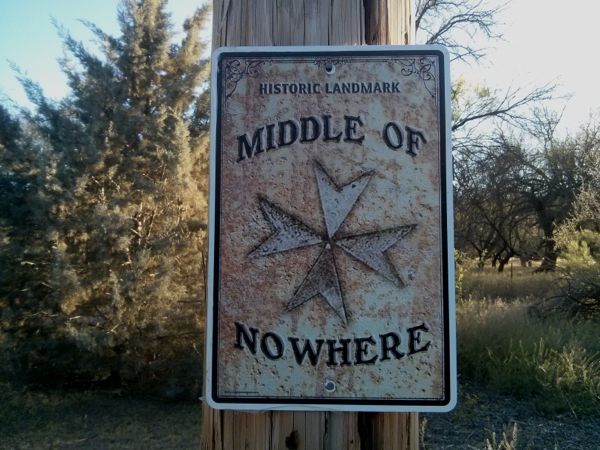

Two years ago in April, Tom and I rented a 100-year-old stone cabin in Cascabel, Arizona, in the San Pedro River Valley, a couple hours east of Tucson. To the uninitiated this might be considered the middle of nowhere. The nearest grocery store is 45 minutes by car, the best road here is unpaved, water is scarce, and a census might have to include cows to break 300. It didn’t take long, though, for us to realize that Cascabel is actually somewhere, and not only that, it is somewhere special. Even after just a week we knew that we wanted to come back. It took us two years to do so, but on March 1st we arrived for a seven-week stay.

Downtown Cascabel

There is so much to say about this place—both the land and the community— that I get tongue-tied just thinking about it, so I am going to come at it through the back door. Instead of painting the grand picture, I am going to start with some humble bits, sidling up to it with a little whistle, as I have seen some people here approach a cow they needed to move.

--------------------------------

After having been in the desert now for the last four months, we are getting used to the "don't touch that" rule, whether it is the furry-looking cholla cactus, or the cat-claws of the acacia, or the long spikes on the mesquite trees. It seems best to just assume that rule applies to all plants and, well, pretty much anything that moves. Having grown up in the soft-and-friendly Pacific Northwest, I like to touch things, and I have to be reminded to keep my hands in my "Haydn-pockets" here.

Every Wednesday there’s morning coffee at the community center, followed by a work party at the community garden. Our first Wednesday here, the guy who sits down at our table is recovering from a scorpion sting on his foot. I am talking to someone else and can’t hear the details, but the length of his story and the size of his gestures suggest that he has been in a lot of pain.

I heard about fire ants on my previous visit, so I am careful to avoid ant mounds when I am walking. When we are visiting a neighbor here, looking at the native grass plantings he is tending in his restored pasture, I stop for a closer look at some unusually large black ants swarming in and out of a hole in the ground. "Oh, those,” he says, telling me the name, which I can’t remember now. “Don't mess with those, their bite is way worse than a scorpion sting!" Move along, in other words. Maybe over by that prickly pear cactus or in that stand of velcro grass. Or in a patch of that bristly plant with the yellow flowers that someone warned me would give me hives if I touched it without gloves.

Javalinas look like small, vertically-flattened, pointy-toed pigs that wander around in packs looking for mud. Mostly they seem interested in hiding, and the few times I have seen them it was from the rear as they ran hysterically away from me. But one woman mentions that she doesn't like to walk along the river in a place where the javelinas gather, not so much because they are dangerous, really, but because "javelinas don't have a sense of humor." Woody, the ranch's herd manager, tells a story of one angry javelina waking him up from a nap in the fields and chasing him into the stock pond. His description of the smell of the sludge he stirred up from the bottom of the pond when he fell in made me think that being bitten by the javelina might have been preferable.

After moving cows one day we sit in a little house next to the corral having cookies and cheese and I notice a good-sized spider (a solid inch in diameter with all the legs pulled in) on the wall over our host. Spiders aren't a trigger for me the way snakes are, but I think she might like to know about it so I mention it. Oh yeah. That guy is just a baby. It is deadly poisonous, of course, and moves really fast, so I am waiting until I can focus on it to catch it.

Oh, and I have now seen my first rattlesnake. I should have been forewarned, as Cascabel means “rattle” in Spanish, and refers in this case to the tail-end of a rattlesnake. Sure enough, our first night here I “discovered” a good-sized rattlesnake coiled up by the end of our trailer, and get my first lesson in snake catching and moving.

A few weeks ago most of the community gathered for a memorial service for a very dear friend of theirs who recently died. After a spacious hour of silence, meditation bells, and remembrances we sit for potluck lunch. The woman next to us asks us how we are doing here, and we tell her how much we are taken by the valley, to which she responds, “Well, with the warmer weather, you will need to watch out for the Kissing Bugs." Kissing Bugs! What? No one told us about Kissing Bugs. Turns out these are stink bug look-alikes that hide behind your cushions and come out at night to bite you while you are asleep, attracted evidently by the smell of your breath. Their saliva has a little anesthetic in it so you don't even feel them when they "kiss" you and they are able to fill to exploding on your blood like a leech. Great. Bed leeches.

The next Wednesday I am back at the community garden when someone walks by the young man who is helping with our tomato transplanting team. "I hear you got hit by a burn worm," he says in the sort of somber tone you might use for someone who has had a limb amputated. Burn worm?!? What now? Turns out these are some kind of caterpillars (also known as mesquite stinger caterpillar) covered with stinging hairs, that fall out of the trees and feel, as the unfortunate young man reported, like four bee stings at once. At least now I know how to treat it, which is to apply duct tape to the burning spot and then rip it off to pull the little stinging hairs out of your skin. This is also supposed to work with cholla glochids, though my previous experiences with sports tape make me wonder if this cure might add insult to injury.

I say all this to emphasize how amazing this place is. That even though the list of poisonous, prickly, and painful things to be avoided is longer than our trailer, I still wake up every day feeling like I have landed in paradise. Perhaps the threat of harm makes me pay more attention and take less for granted. Perhaps there is a kind of awe at the lengths things go to survive in harsh environments. Perhaps there is a longing to be as at home in this wide, arid land as the creosote bush and the cactus.

All I know is that this land feels deeply, vibrantly alive—an understated aliveness mirrored by the people who choose to live here. I have experienced a profound gentleness in many of the people here, coupled with a willingness to act decisively in service to what they believe in. There is a commitment to being partners with the land, rather than the land being a possession or only a means to making a profit. These ideals seem to arise at least in part from the desert itself, which is absolutely unforgiving and absolutely itself, while also offering an intense spiritual aliveness.

Not everyone who lives here ascribes to these ideas. There are many different faces to Cascabel, and what you see depends on where you stand and who you talk to. What is clear to us, though, is that we are here to learn—about generosity, about community working together, about how to live in challenging circumstances, and most of all about the land.

--------------------------------

Tom and I are staying at a ranch which is the central location for Saguaro-Juniper, the cattle-raising part of this community, and have parked our trailer amidst the welter of houses, trailers, corrals, sheds, horse trailers, trucks, and the kind of equipment and raw materials that accumulates on every farm. We feel so lucky to be here. To the west we can walk to the San Pedro River and can get to an area where the riverbed has year-round water. To the east we can walk for miles out into the saguaros and creosote bush of the desert. Our hosts are some of the original founders of this community and it has been a pleasure to get to know them and hear their stories.

This is also the location of the Sweetwater Center, the organization that I am volunteering for while we are here. I am helping with some pasture improvement projects as well as caring for two new plantings of pollinator plants. What this really means is I do a lot of weeding, which is something with which I have loads of experience. I am surprised at how much I am enjoying it. I think it feels good to just do something familiar, simple, and rote after six months of so much change.

When I am not weeding or walking in the desert with Tom, I have been immersed in the busy social life of this community. Coffee gatherings, Quaker meeting, potlucks, horseback riding, folk dancing, meditation group, writing group, road cleanup, cheese making, game night, celebrations of all sorts of things, committee meetings, mesquite-pulling work parties, conservation work, and tending the community garden all somehow get squeezed into the short weeks around here. The result of that, though, is that after only six weeks here, I have met just about everyone who lives along about a ten-mile stretch of the dirt road.

There is so much more to say about this place, but it will have to wait for another post. I am still digesting the incredible vastness of the desert, the life-giving presence of the river, the principles of the people who have been drawn together in community, and the work of the organizations that have formed around the intention of tending this valley and its inhabitants.

In a week we will pack up our trailer and move on. We aren't sure where we are headed or what the next five months will hold for us. We don't know when we might come back here. But the people and the land are in our hearts now and give us strength. We feel different after being here—a little more relaxed, a little more aware, and warmed by many memories.

May 17, 2017

May 17, 2017

Creatures

Creatures