Part 5: The story of our lives

March 28, 2019

March 28, 2019

When I was training to be a therapist in graduate school, our first assignment was to write our autobiography. This was partly to see how we were shaped by the first system we lived in—our families. But I think an even deeper purpose was to show us that our very idea of who we are is a story, and one that we largely construct ourselves.

In the second year of graduate school we revisited and updated these autobiographies. I found that some things that seemed important to include the first year no longer mattered the second. Through the work I had done, some hurts had healed. My story had changed. Perhaps only a little, but those changes gave me a lot to think about, and led to many more small changes over the years.

With the death now of both of my parents I feel the need to update my story yet again. So much changes with their passing, not least of all my ideas about myself. I feel a strong urge to write, to make meaning of these events, to integrate this new information. Things change. Nothing stays the same. Even parents pass away. We will follow too, soon enough. Given this, what matters to me? Where do I want to put my energy? Where is this story headed?

*******

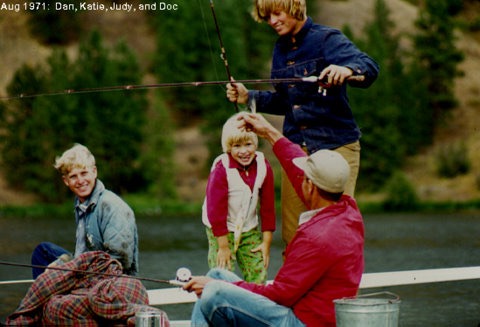

My story of my life with Dad begins with a mixture of pleasure and discomfort. Especially as a little girl I have warm memories of playing together: learning to ski, playing hockey on the frozen lake, fishing for perch with worms we dug ourselves in the mud by the spring, playing Yatzee on winter evenings, or curling up with him on the couch to read the funnies. But I also have memories of being uncomfortable around him.

Dad was an unusual person. He had definite opinions that were often outside the norm. He didn’t communicate easily, though he talked a lot to the people closest to him, and he wrote voluminously on topics that he was wrapped up in. He wasn’t that good at empathy or seeing other people’s gifts—or if he was, he didn’t waste time expressing it. He was better at talking at you than with you, and if you wanted a conversation with him you’d better find a topic he was interested in.

Dad had strong principles and was a champion of truth, which meant he was bothered by the natural inconsistencies of government, religion, or people just trying to live together. And though he was usually pretty calm, his emotions were intense when ignited. When he got started on something that involved both his principles and his emotions, he was like a rat terrier with a rat—he just wouldn’t let go. There was an obsessive side to him that led him to spend years of his life trying to “straighten out” various disputes. And when he was involved in one of these issues, it took up all his time and all the space in his mind. As I said, he talked a lot to those closest to him, and one of the reasons Mom knit so much was to have something to do with her hands while he was talking to her about whatever dilemma he was immersed in. Mealtimes were dominated by the topic that was uppermost in his mind. And there are stacks of comb-bound booklets left in his office that are several feet tall (each), on disagreements he was involved in over water rights, government regulations, or religious differences.

Quite frankly, as a girl I was afraid of him, especially at the dinner table where his obsessions got aired as lengthy monologues or rhetorical questioning. My story at that time didn’t include any ability on my part to protect myself from his emotions and his need to work things out that were weighing on him, and I often felt trapped and voiceless. I mostly outgrew the fear (mostly), after a long struggle to develop my own answers and my own inner resources. In recent years I felt a lot of love for him—and also a growing realization of our kinship and how similar we were in our essential values—but even then it was hard to know what to do with him or how to express that love.

Largely, this was because Dad wasn’t that comfortable with expressions of affection. At his memorial, a grandson told a story about his amazement when he actually got a hug from his grandpa—sometime in his 20’s. As a young woman, my memories of Dad expressing his appreciation are spare. I remember getting my first “grown-up” clothes in high school, a tailored gray suit-jacket and skirt, but when I wore it to show him, his only comment was, Well, you won't be doing any carpentry in that. As I tell this story now, it seems ridiculous that I couldn’t see that he meant this as a compliment, but at the time I felt offended and hurt. My story wasn’t big enough yet to include his kind of love.

This summer, when we stayed with Dad for three months, Tom and I lived in our trailer and would come into the house to share a meal with him, or read together, or watch the news or Lawrence Welk. Dad would head to bed around 7:30 and he and I had a ritual way to say goodnight to each other of reaching out and holding hands for a moment. At the beginning of the summer I would give him a hug, but somehow it evolved into this short hand squeeze, which seemed like just the right distance for both of us. I still remember the feeling of his hand, so roughened by farmwork that it felt like he was wearing leather gloves. I felt so loved by that simple gesture. And when I just let that into my heart my story changes again.

Now, after his death, none of the past seems to matter much at all. It feels like some kind of artificial barrier has been lifted and there is just a field of love around me now from him. I spent so many years of my life cowed by him, then so many years developing the inner strength to be my own person with him. Then all of a sudden the whole story is turned upside down, irrelevant, and all that is left is this sensation of this warm presence behind me, all around me.

Our summer together was the rehearsal for this. My need to be right dissolving in the sprinkler-moving antics. My need to be helpful dissolving in his ownership of his own fate. My story of his lack of affection dissolving in my reaching out and having him reach back.

When we left the farm, he dressed up in his town shirt and stood in the driveway leaning on the ski pole he used as a cane, watching us pack up and fold the trailer away. When we were ready to go, he and I had a minute alone while Tom got something out of the house. We stood silently for a moment, then as he heard the door to the house slam, he reached out, not with his hand, but with his whole body, and squeezed me hard against his chest in a tight hug. Then he let go, and through my tears, I could see that he was saying goodbye, probably for good. And in that goodbye, he was giving me the only real gift he ever had to give.

I go forward with my life, however my story unfolds, wrapped up in his eternal love.

-----------------------------

This is my last post in this series on Dad's death. I have appreciated having a place to write where there are people out there receiving these words. Grief is both deeply personal and completely universal; it is something that you experience alone, and yet feels lighter for being shared. I am grateful for all of you reading this. Your presence means a lot to me.

And that reminds me of the joke that one of my brothers kept telling the week after Dad died.

There was a man who was at the funeral for his wife. Toward the end of the funeral he got up and asked, "Is there anyone who would like to say a word?" A friend of his got up, faced the congregation and said: "Plethora." Then he sat back down. The bereaved man teared up at hearing this and said, "Oh, thank you. That really means a lot!"

I think Dad would have liked that one.