A pause for thanks

November 28, 2019

November 28, 2019

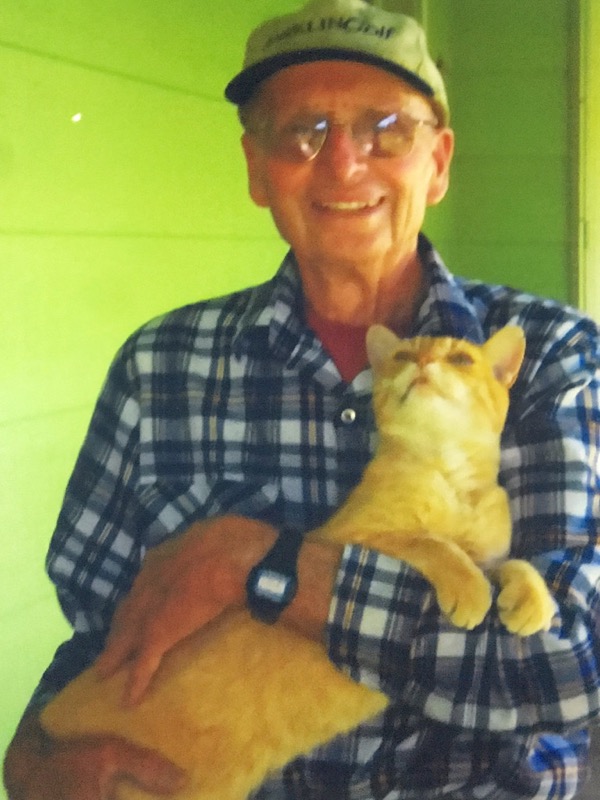

For the last few months I have been sorting through boxes of papers from my parents’ house, and this, and the upcoming one-year anniversary of my Dad’s death has me thinking about my relationship with him. In the past, I would have emphasized the differences between us. Now I'm feeling our similarities.

As I have said before, my father was very private, and at least in his adult life, only talked to a few people. He liked to be social if there were games involved—ping pong or volleyball or horseshoes—but when it came to talking, it was mostly his family that he turned to: primarily my mother, and while I was at home, me. When he did talk, he tended toward the monologue. It was like he needed a place to unroll all of his thoughts in front of him so that he could understand what was in his head. And then at the end of the conversation he would roll all of them back up again until the next day when he would take them out again as though no one had ever seen them before. My mother—as I said when I wrote about my father last year—did a lot of knitting.

He also wrote voluminously—in longhand on yellow notepads and spiral notebooks, and later on the computer—and then created booklets out of what he wrote, comb bound after he got his own comb binder and copy machine. He wrote about all the different projects that he was involved in: water rights and field burning and property-boundary disputes and taxes. But the subject that he wrote about the longest, and the one he and I always talked about, was religion.

Thinking about this now is odd. On the one hand as a kid, this was upsetting. My dad’s conversations with me felt oppressive and heavy and often left me feeling trapped and taken over by someone else’s life. It took me years to unlearn enough of the passive stance I took toward those conversations to have my own boundaries and direction. And yet those conversations were also the precursor to my own life-long interest in spirituality and my deeply-satisfying work as a therapist.

I had come to peace with my father some years ago, but as I look through his writing I keep seeing new things about our relationship. For example, even just as I was writing this, I realized that he didn’t talk to me about everything. For some reason, it hadn’t occurred to me that he had all kinds of projects going on, but he mostly talked to me about religion. Or perhaps I only really listened to him when he talked about this subject. Either way, that’s news. Either he knew more about me than I realized, or I had better boundaries than I thought, and could tune out things that didn’t actually interest me. Maybe I was there at the dinner table with him, not exactly out of choice, but at least out of inclination.

*******

The other night, late in the evening, I was finishing up reading Dad’s letters to his siblings, and had been talking about my thoughts and reading passages to Tom who was doing something else at the time—working on his pictures or getting ready for bed—and he commented after something I said about Dad, “Boy, you two sure are a lot alike.”

I wasn’t sure I wanted to hear this. I don’t want to be that person who talks on and on at the dinner table long after everyone’s eyes have glazed over. I don’t want to be so compulsive about what I am thinking about that I can’t put it down. I don’t want to make booklets about religion and send them to my relatives and have them not respond.

But when I reflect on it, Tom has a point. I was, after all, talking to him mostly to figure out what I was thinking. I also write a lot, and as I look over old journals I notice how often the same themes come up. And I make books: a row of handmade books of poems and essays sit on my shelf right now, and every few years I organize whatever it is that I am working on into some kind of collection.

Dad didn’t have a public place for his ideas. It hurts my heart a little to see him begin a letter to his brother with a remark about not having heard back about the booklet he had sent to him recently on religion. And I can remember my own reluctance to open letters he sent to me at college because I was pretty sure I already knew what was in them.

I am aware more and more of the importance of having people just listen to you. Mom and I and other people in the family did listen to Dad in many different ways. My sister was better at listening with a tennis racket. My brothers listened through music or ping pong or working together on the farm. I think Dad was happy enough with the avenues he had for self-expression.

But looking through his stacks of writing, and wondering what drove him to work so hard to put his inner thoughts into words, and feeling that same need so strongly in myself, makes me feel especially grateful to have some public place for my writing. In particular, I am grateful to have this blog, which I never would have started without Tom's encouragement; and I am grateful for all of you who read it—your listening, and your letters back to me, encourage me to keep writing. This has been a place where I can "talk out loud" about what I am thinking; and it challenges me to put my thoughts in a form that I can share with other people. Both of these help me know myself better.

I am also feeling grateful for Dad, just for being himself. As time goes on, I appreciate him more. And this is a good thing, because Tom’s right: we are a lot alike, and so if I am going to love myself, I had better learn to love him.

******

In later life my father finally condensed his thoughts into one short piece about his religious position, titled “Religion and Me”, that I think is a good summary of his lifetime of thought. And in a letter he sent me along with the booklet, he wrote a sentence that I appreciate again reading it now: Thanks for being this Philosopher’s Sound Board over the years. I think realizing that he was thankful for who I was goes a long ways toward building that bridge of love over the troubled waters of the past.

Feeling more appreciation for my father isn’t something I could have tried to do. It just happened as a natural result of the passage of time and my continued interest in my dad's life. Understanding and empathy come from engagement. And I believe that we are each engaged by what we need to be engaged with—that we can’t help it. That what we each need to look at grabs us by the collar and won’t let go. And so if we turn toward whatever has us in its grip, it is likely that this will lead us in the direction of love. Because really everything leads in this direction. Even hatred. Even separation. Even our own stubborn clinging to everything we know. Help is there where we least expect it.

Dad did this—he turned toward what gripped him, to the best of his ability. And I think that talking and making booklets helped him to distill his life into a place of more acceptance and humility. And that helps me see that the things that I do naturally—no matter whether from compulsion or interest—will do the same for me. And I am remembering the phrase with which Dad often ended his correspondence—with love and affection—which makes me think now that he might have saved his best point for last.